The Art of Marbling

Marbling is a kind of duet between artist and water. It originated in the Far East, developed in Persia and Turkey, and enamoured European travellers in the early 1600s. A few decades later some of the greatest minds in London gathered together to learn how it worked.

On 8th January 1662, members of the “College for the Promoting of Physico-Mathematical, Experimential Learning” (later to become the Royal Society) met in Gresham College in Bishopsgate, London, for their weekly meeting. This evening it was John Evelyn, one of the twelve founding members of the college who would address the gathered crowd. His topic was “Marble Paper”.

Evelyn and his contemporaries in the 17th century understood paper marbling to be a Turkish or Persian art: “The Turks have a pretty art of chamoletting of paper, which is not with us in use” wrote Francis Bacon in his encyclopaedic tome, Sylva Sylvarum, published posthumously in 1626-7, and while by the mid-17th century it was common to see marbled paper in England, it was still an import (usually via the Netherlands) whose production remained mysterious. Eveyln’s contemporaries may have owned books with marbled endpapers, and now his audience would discover the method of their production.

Sitting between dissections, demonstrations and debates, Eveyln’s choice of lecture is also a reminder of the close alignment of art and science; just as the scientist relies on imagination and creativity, the artist is lost without experimentation and, especially in the case of marbling, an understanding of chemicals and their properties.

The lecture was eminently practical. A surviving manuscript in Evelyn’s own hand reveals precise and clear instructions which still today serve as an excellent introduction to marbling.

First he describes the creation of a “size” from water and tragacanth, a gum derived from the sap of species of legume common in the Middle East. This thickened water will allow the pigments to float on top, ready to be manipulated and then transferred to the paper. Evelyn suggests using four colours, indigo (blue) and orpiment (yellow), which are to be combined to make the third colour, green. The set should be completed with a “fine red lake”. "Lake" pigments are organic rather than mineral, made from plants or insects. He recommends mixing “red lake” with “the raspings of Brassil”, or ground brazilwood, which is the red-coloured core of the trunk of a sappanwood, or brazilwood tree.

To make them suitable for marbling, the pigments are to be mixed with ox-gall. Derived from the gall-bladder of a cow, this substance is a dispersant and allows the pigments to flow, or “dilate” as Evelyn puts it, on the surface of the size. With the prepared pigments in “Gally pots”, straight sided, beaker like vessels, Evelyn instructs the marbler to sprinkle the colours onto the tray of size one by one: blue, red, yellow and finally green. To achieve the “agreable chambletting” one is now to swiftly drag a pointed stick in a zig-zag motion across the tray, before taking a comb in both hands and carefully pulling its teeth through the pigments. Evelyn suggests making the comb oneself, by cutting a length of finger-thick wood to the same size as the tray and inserting pins (“such as women use”) into it at quarter inch intervals. The knack of laying the paper evenly on the water’s surface is one that requires dexterity and practice, explains Evelyn. A short time, “two or three pulses”, is ideal for the pigment to adhere to the paper yet prevent it becoming soaked.

John Evelyn (1620-1706) is pictured here in a 1687 portrait by Godfrey Kneller. The portriat was presented to the Royal Society by Evelyn’s wife, Mary, shortly after his death. © The Royal Society

John Evelyn (1620-1706) is pictured here in a 1687 portrait by Godfrey Kneller. The portriat was presented to the Royal Society by Evelyn’s wife, Mary, shortly after his death. © The Royal Society

Manuscript of John Evelyn's lecture on "Paper Marbling"

Manuscript of John Evelyn's lecture on "Paper Marbling"

The pattern described in Evelyn’s lecture sounds most similar to that known in Britain as Old Dutch. The zig-zag drawing of the colours and the combing across the surface of the water would create an effect as shown in the image above.

The pattern described in Evelyn’s lecture sounds most similar to that known in Britain as Old Dutch. The zig-zag drawing of the colours and the combing across the surface of the water would create an effect as shown in the image above.

Camlet (or chamblett) was a cloth originally made of camel hair (or perhaps angora) and silk and imported from the East. By the 1700s a similar style of cloth was being manufactured in the Low Countries, France and England. A 1765 dictionary reveals the variety of patterns that could be found on camlet: “Some are dyed in the thread, others are dyed in the piece, others are marked or mixed; some are striped, some waved or watered, and some figured”. It seems clear that the marbled paper resembled the rippling, fluid patterns that Eveyln and his contemporaries were familiar with from camlet fabric.

“The Turks have a pretty art of chamoletting of paper, which is not with us in use”

Francis Bacon (1561-1626)

This is an Album Amicorum, a scrap book where people would collect messages and illustrations from friends. It was in books like this that marbled papers from Turkey first arrived in western Europe in the early 1600s. This example dates from the early 1700s and once belonged to the Swiss nobleman Hans Wilpert Zoller. Metropolitan Museum, of Art, New York.

This is an Album Amicorum, a scrap book where people would collect messages and illustrations from friends. It was in books like this that marbled papers from Turkey first arrived in western Europe in the early 1600s. This example dates from the early 1700s and once belonged to the Swiss nobleman Hans Wilpert Zoller. Metropolitan Museum, of Art, New York.

This is an Album Amicorum, a scrap book where people would collect messages and illustrations from friends. It was in books like this that marbled papers from Turkey first arrived in western Europe in the early 1600s. This example dates from the early 1700s and once belonged to the Swiss nobleman Hans Wilpert Zoller. Metropolitan Museum, of Art, New York.

This is an Album Amicorum, a scrap book where people would collect messages and illustrations from friends. It was in books like this that marbled papers from Turkey first arrived in western Europe in the early 1600s. This example dates from the early 1700s and once belonged to the Swiss nobleman Hans Wilpert Zoller. Metropolitan Museum, of Art, New York.

This is an Album Amicorum, a scrap book where people would collect messages and illustrations from friends. It was in books like this that marbled papers from Turkey first arrived in western Europe in the early 1600s. This example dates from the early 1700s and once belonged to the Swiss nobleman Hans Wilpert Zoller. Metropolitan Museum, of Art, New York.

This is an Album Amicorum, a scrap book where people would collect messages and illustrations from friends. It was in books like this that marbled papers from Turkey first arrived in western Europe in the early 1600s. This example dates from the early 1700s and once belonged to the Swiss nobleman Hans Wilpert Zoller. Metropolitan Museum, of Art, New York.

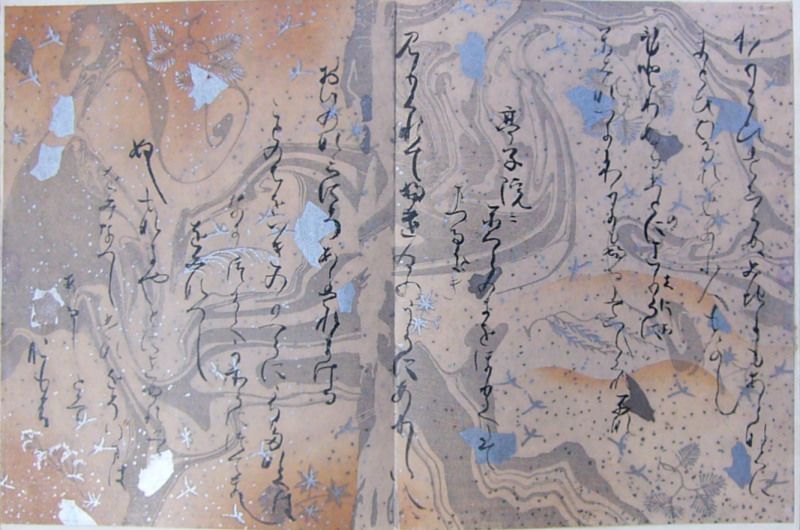

Album of Calligraphies Including Poetry and Prophetic Traditions (Hadith) by Calligrapher Shaikh Hamdullah ibn Mustafa Dede Turkish, ca. 1500. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Album of Calligraphies Including Poetry and Prophetic Traditions (Hadith) by Calligrapher Shaikh Hamdullah ibn Mustafa Dede Turkish, ca. 1500. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A $20 bill issued by the Continental Congress in 1775 with a marbled strip on the right hand edge. This image is from the University of Notre Dame and available through Wikimedia Commons.

A $20 bill issued by the Continental Congress in 1775 with a marbled strip on the right hand edge. This image is from the University of Notre Dame and available through Wikimedia Commons.

A $20 bill issued by the Continental Congress in 1775 with a marbled strip on the right hand edge. This image is from the University of Notre Dame and available through Wikimedia Commons.

A $20 bill issued by the Continental Congress in 1775 with a marbled strip on the right hand edge. This image is from the University of Notre Dame and available through Wikimedia Commons.

Evelyn and his contemporaries used the term “Marble Paper” because of the tendency of early European travellers to compare the patterned paper to the veined appearance of marble stone. Yet the names of the craft in Turkish (ebru) and Persian (abrī) both refer to an art form of the “clouds”. This nomenclature reflects not only the swirling, nebulous patterns, but hints at the meditative and mystical connotations of marbling.

There is certainly something elemental and ethereal about the craft, in which the practitioner enters into a kind of duet with the medium of water. Creating the desired patterns requires a very delicate touch, and an understanding of the response of the liquid to different kinds of agitation. Once achieved, the pattern can be transferred only once in a process which transforms a transitory, intangible suspension of colours into something permanent.

The earliest surviving examples of Middle Eastern marbled paper date from the 15th century. They were manufactured in greater Iran and used to decorate manuscripts, or as a background for calligraphy. An artist named Muhammed Tahir is credited with having brought innovations to the practice and establishing the kinds of patterns and colour palettes which the early European travellers so admired.

Once the practice of marbling had firmly arrived in Europe, uses of the craft beyond the purely decorative were explored. In the 1690s, a few decades after John Evelyn’s demonstration of marbling to the Royal Society, the Bank of England made use of marbling as a security device on paper money. With only a privileged few having access to demonstrations such as Evelyn’s, the process of marbling remained entirely mysterious for the majority. This, along with the fact that each marbled sheet is a monotype, a unique and irreplicable print, meant that the craft seemed to have the potential to guard against the counterfeiting of paper money.

It did not prove effective, however as only a few weeks after the introduction of marbled bank notes by the Bank of England in 1695, the Bank’s Court of Directors recalled their use, having discovered forgeries in circulation.

The principle was tested once more, however, in the early days of the American War of Independence when the Continental Congress issued its first $20 bills which featured a hand marbled margin as a security device.

Within a century of John Evelyn’s 1662 lecture, England already had the beginnings of its own marbling industry, with a marbling workshop arriving on Fleet Street, the heart of the London printing trade, in the 1780s. One of the main uses of marbled paper, as a key component bookbinding, would remain relevant for well over another century, and some popular “how-to” books published in the 1800s would bring the art of marbling to an even greater audience. However the 19th century heyday of the marbling industry in countries like England would be relatively short lived. Demand for marbled papers fell sharply as books became more mass-produced and less decorative.

While there remains a small demand for marbled paper for use in specialist bookbinding and book conservation, practitioners of marbling in the UK are nowadays likely to be involved in producing luxury objects such as stationery, bespoke wallpapers or decorative items. The UK Charity “Heritage Crafts” has designated marbling an endangered art, with less than 20 people generating their main income from paper marbling.

Yet the mesmerising patterns continue to inspire admiration and creativity, and although the Royal Society may no longer offer marbling demonstrations as it did in 1662, many practitioners regularly share their expertise, and supplement their income, by offering hands-on workshops. In London marbling workshops are offered at places like The Goodlife Centre, through TTA (Traditional Turkish Arts), and at Marmor Paperie. City and Guilds Art School has run an intensive 5-day introduction to marbling as part of its programme of short courses in the summer and may do so again in 2025.

SUMINAGASHI

(sumi = ink, nagashi = floating)

Suminagashi is the Japanese iteration of marbling and is known to predate the Persian or Turkish practice. Examples of Suminagashi exist from the 12th century, although the art is mentioned in East Asia as early as the 9th century. It is not known whether cultural encounters spread knowledge of the craft, or whether the practices developed independently. A key difference is that suminagashi is carried out using pure water as a base, there is no use of a thickener. Specialist inks which contain oily substances are floated on the surface of the water to create patterns, often based on concentric rings. Historically suminagashi used just a few colours, primarily a black ink which is traditionally made from burned pine wood, or blue (indigo) or red (vermillion).